Raymond Chandler famously hated science fiction, saying “They pay brisk money for this crap?” However, it has recently come to light that Chandler secretly wrote a series of stories and novels starring a robot detective. He then burnt all the manuscripts and went on writing his noir masterpieces. Unknown to Chandler, his housekeeper had managed to save some of these discarded manuscripts from the grate in his study, preserving the tales for future generations.

The first of these stories was recently unearthed by author Adam Christopher. On the topic of how the manuscript made its way from Chandler’s study in California to Christopher’s home in England, Christopher is suspiciously quiet.

This novelette was acquired and edited for Tor.com by editor Paul Stevens.

I pulled into the curb and stopped the car. It was dark and raining like nothing else, and when I killed the headlights I couldn’t see anything in particular. Just the night outside, the street light filtering in multicolored rivers through the water as it poured down the windshield. The rain had started heavy and gotten worse and now it was like there was someone lying on the roof of the car, pouring water over the glass in the same way they might lean out of an apartment window to water a particularly difficult-to-reach planter.

For a second I remembered a guy I once met who leaned out of a high window a little too far. Or maybe more than a little.

And then it was gone. Overwritten. Just another fragment.

I picked up the phone that sat cradled between the driver and passenger seats, pulling the coiled cable free from itself as I pressed the earpiece to the side of my head. The phone clicked in my ear and began to hiss, the sound fighting against rain. It was like someone was shoveling coal into buckets out there.

“So I’m here,” I said.

The voice on the other end laughed, and the image came back to me: your favorite aunt, the one who smoked too much and sat out on the porch on summer evenings wearing a skirt that was too short, and when she put her bare feet up on the rail, rocking back and forth in her rocker, she’d laugh and blow smoke out of the corner of her mouth.

It’s the image I always got when I talked to Ada. I didn’t have much of a memory and the image wasn’t mine, so it must have been one of his. Thornton’s. I guess he used his mind as the template for mine, although I didn’t know this for sure. Maybe one day I’d ask him. If I remembered, which was unlikely, so there you go.

“You’re early,” said Ada. Her voice didn’t come from the phone. I ignored this fact and held the phone to my ear anyway.

“It’s raining,” I said.

“There’s an umbrella in the trunk.”

“No, I mean I left early.”

“You lost me on that one, Ray.”

“So I gave myself extra time in case I got lost, because I don’t much like driving in the rain. So now I’m here, wherever ‘here’ is.”

“You’ve got one minute.”

“So not that early, then.”

I peered out of the windshield. The street was lit up like it was Christmas, the red and white of the flashing signs and neon mixing with the constant yellow wash of the sodium street lamps. None of it helped. The whole world on the other side of the glass was twisted shadow, the rain reducing everything in my view to just shapes and movements. Cars cruised. People walked. Hunched over, against the rain. Maybe some had umbrellas. I couldn’t tell and I couldn’t have cared less.

“I hate the rain,” I said into the phone, and listened as Ada laughed inside my head.

“Afraid you’ll rust, detective?”

“It’s not that. You know it’s not that.”

“Thirty seconds.”

“Until what?” I switched the phone to my other ear and turned in the driver’s seat, seeing maybe if the view out the rear was any better. It wasn’t. It was raining as hard at the back of the car as it was at the front. A quick check confirmed it was also raining on the right and on the left.

Ada didn’t say anything, but I could hear her ticking away, like the fast hand of a pocket watch.

“You know,” I said, “for a secretary you sure as hell don’t tell me much.”

Ada laughed at this and I would have sighed if I could, but I couldn’t. I wasn’t made that way. But I knew what a sigh was. People did it plenty when I was around. I even thought I knew how to do it, the way your mouth moved, the kind of shape you had to make with it. Thornton again. He sighed a lot too. I must have caught the knack from his template.

“Need to know, Ray,” said Ada. “And less of the secretary, if you please. I’m your partner, right? Just because I stay put and answer the phone.”

Partner? That was a new one. “Uh-huh,” I said.

“And about that.”

“About what?”

Ada sighed. She could do that even if I couldn’t. “You know you don’t need to pick up the phone to talk to me, right?”

“Habit,” I said. But that wasn’t true, so I corrected. “Okay, not habit. Programming.”

“Someone had a sense of humor.”

I shrugged. “Gives me something for my hands to do.”

Then the passenger door swung open quick and a man got in. He was wearing a tan trench coat colored at least two shades darker than factory issue thanks to the rain, and when he tilted his head as he brought his gun out from inside his coat, the rain ran around the brim of his hat and splattered onto his knee.

I froze with the phone in my hand and my eyes on the surprise visitor. I guess this is what Ada had been talking about.

I heard her laugh and she said “Good luck,” and then the phone was dead. Like it had ever been alive.

“Come on,” said the man. He pointed with his gun, which I took to mean I should put the phone down, so I put it back in its cradle. I tried to keep the cable neat but it twisted all by itself. Never mind.

“Come on what?” I asked, but I had a fair idea. The man nodded towards the windshield, towards the rain and colored lights. Then he lifted the gun up and tapped it against my cheek twice. Don’t ask me why he did it, but after he did he smiled like he was pleased with himself and the dull metal-on-metal tapping sound his action made, then he nodded forward again.

“Just drive,” he said.

I started the engine and pulled out into the street and drove like the nice man with the gun said.

***

The man with the gun had relaxed a little by the time we’d driven all over town and back again. We weren’t lost. He knew where we were going, or at least he said he did. I don’t know. I didn’t ask. I figured either he was trying to shake a tail that I knew wasn’t there, or he was trying to make sure I couldn’t find my way back later to wherever we were going now. That wasn’t going to work, mostly because I’m a machine and I can remember lots of stuff that the guy with the gun probably couldn’t. And also because when we got to where we were going, I knew exactly where it was.

Playback Pictures, Hollywood, California. Any dumb schmuck with a positronic brain or a copy of the Los Angeles telephone directory could have found it, because it wasn’t hard to find. I lamented the waste of gas driving all over town for the last two hours, but the man with the gun didn’t look like he wanted to be interrupted, so I didn’t bring it up. We cruised past the main gates and down a side street, then through a smaller trade entrance that I’m pretty sure was supposed to have been locked up. It was getting late and the place was deserted. We pulled up in the middle of the parking lot and my mystery passenger sat there with the gun pointed at me and his nose pointed out the window on the passenger side. He was looking for something. Or someone.

On the way over, he’d relaxed. It was a long drive, after all. He managed to keep the gun on me most of the time, held below the dash to keep it out of sight.

In fact, he was more than relaxed. He was as chatty as a talk show host. I didn’t speak, but the less I said, the more he did, like he was compensating. Maybe that was how it worked. Maybe I should have been programmed to be a newspaper reporter, the way this guy was going on while I did nothing but keep the car on the road. He talked about restaurants we drove past. He liked to eat and he liked to drink, I got that. I thought that might be nice. Eating and drinking. People seemed to go on about it a lot. This guy in particular.

After a half hour of drive-by restaurant reviews he started whistling, and after a half hour of drive-by whistling he finally turned to me and looked me up and down. The gun was still in his hand.

“Don’t see many of you around, y’know?” he said.

I checked the rearview. We were on Santa Monica Boulevard doing a steady rate of knots. There were plenty of other cars on the road but none had been following us. I know, because I photographed all the license plates I could see as we drove and was comparing them against each other even as I spoke to the guy with the gun.

“Private detectives?” I asked.

“Naw,” he said. Then he waved his other hand like he trying to hurry someone up. Maybe that someone was him. “Robits. Y’know. Like you, Chief.”

For a moment I wondered why Ada never called me Chief. Then I wondered how Ada knew this guy with the gun and why she never bothered to tell me anything.

“Oh,” I said. “Robots. Right.” I said the word right, because it seemed important that I should. The guy with the gun didn’t notice. He was still rolling his other hand.

“Yeah. See,” he said, and then he stopped, and then he kept going. “See, used to be there was a robit what worked the traffic down on Melrose. Y’know, that big junction where it all goes to shit.” Now the gun was pointing somewhere else and he mimed ‘all goes to shit’ with both hands like a master sculptor working in clay. Then he shook his head and pointed the gun back at me. But I could see his heart wasn’t in it. For the most part, I had settled into my new job as chauffeur.

“They had them on busses too. Y’know, tickets and stuff. Even was one down on the corner at the newsstand. I swear it. Kid next door used to buy comics from him every freaking Wednesday. Huh.” The man shook his head and said “Every freaking Wednesday” again to himself and then he turned to me. “So what happened to them all, Chief? Something must've happened. Left here.”

I took the corner smooth as silk. That’s one thing I liked about the car. The suspension was custom. Smooth as silk. Had to be, considering the driver weighed nearly as much as the vehicle.

“Didn’t work out,” I said. The man nodded. He seemed interested so I kept talking. “The public program included lots of different phases—traffic, public transportation, sanitation. All government to start with, then came private investment and some cooperative projects. Office work. Stores and warehouses.”

“And newsstands.”

“And newsstands.” I wasn’t sure that was right but he was the one with the gun so I wasn’t going to argue. I also wasn’t going to point out that the gun wouldn’t be much use against me, even point-blank. He seemed like a nice class of crook and I didn’t want to disappoint him.

“Didn’t work out, huh?” he asked.

“Nope,” I said. “People didn’t like robots. Not really. Preferred talking to other people instead of machines. And robots have limitations, too.”

The man with the gun nodded vigorously. “Turn right here,” he said, and then he said “So you’re one of the lucky ones, huh?”

I turned right and thought about his question and whether I considered myself lucky. I hadn’t thought about it like that. I just . . . was, and that was that. Nothing more to it. The last robot rolled out of the lab. The first of a new class of machines with the sum total of one completed unit. Was that lucky? I thought maybe I should ask Ada about it some time. She was the one with the connections. She understood people better than I did so maybe she was the one who got the luck while I was the one who got stuck behind the wheel of the car, driving around a guy with a gun.

The guy with the gun reached inside his jacket and pulled out a hip flask. It was silver and I got a good look, but there was nothing on it. No monogram. No initials. No name, address, phone number, social security number. Unlike me. I had some of those at least punched onto my chest plate. Next to the detective shield.

“Hey, you wanna? Oh no, I guess not.” The man pulled the offered flask back towards him and took a slug, then returned it to his pocket. “Hey, mind if I . . . ? Oh no, I guess not.” The man pulled out a pack of cigarettes and laid them on his lap and then he squirmed in his seat as his free hand delved into the front pocket of his pants. The hand emerged eventually, clutching a book of matches, along with a small mound of pocket lint.

I don’t drink and I don’t smoke. Doesn’t mean I can’t taste and smell. I didn’t like the idea of the car filled with smoke, but like I said he was the one with the gun. Even if the gun was useless, I figured that gave him certain privileges.

I took a photo of the matchbook. Figured it was the thing to do, even if I never saw it again. I wasn’t doing anything else but driving at the time so it wasn’t much bother. I also took a recording of the man’s voice. Because that seemed appropriate as well. He had no clue I’d done either, but then I didn’t expect him to.

Being a robot had certain advantages.

“Where you from, anyway?” he asked.

“I’m a local boy,” I said and the man laughed and shook his head.

“You ain’t fooling nobody, Chief! That accent. You’re from out East. Oh yeah. I knows it. East.”

“If you’re asking why I sound like I’m from the Bronx, then—”

The man sighed like he was appreciating a fine painting or a particularly good return on a bet at a horse race.

“I knew it,” he said, and puffed on his cigarette. “The Bronx,” he said, and he said it like he really meant it. Like he had never been there.

The accent was programmed and I had never been there either, but like I said, he had the gun and he seemed to be having a swell night, so I didn’t want to disappoint him.

An hour later and he’d smoked another four cigarettes. The spent matchsticks sat in the ashtray in the console between our seats, a chrome bowl just in front of the telephone. If he’d seen the telephone, he hadn’t made a comment. He’d been impressed by the idea that I sounded like I was from the Bronx, and he didn’t seem to mind too much that he was sharing a ride with a machine. Maybe he thought all robots had phones in their cars, like that was a thing. Maybe he thought I’d come all the way from New York just to drive him around downtown LA.

We sat in the dead parking lot until the rain stopped. By this time his gun was resting on his leg. Maybe he’d been told to hold it on me, like it was part of the deal. Like it was also part of the deal that all robots had telephones in their cars and spoke like they came from one of the Five Boroughs.

The lot was filled with puddles as big as fish ponds and as black as the gun on my passenger’s knee. The buildings nearby were large and low, their few windows dark. They were film studios, the backlot of Playback Pictures. A few sodium lamps were dotted around the access roads, but they did little to illuminate the situation.

There were a couple of other cars parked nearby. A truck, too. But it was late. The cars and the truck were in it for the long haul and there was no sign of anyone around.

Then he leaned forward.

“That’s him,” he said, and he pointed with the hand that was holding a new cigarette.

There was a guy in a coat and a hat walking toward a door in the side of the one building. He was walking fast, head down. He wasn’t keeping to the shadows, not on purpose, but it was dark and there was nobody around anyway, so it wasn’t like he really had to try very hard. But we could see him from the car. He walked like he was getting rained on and didn’t like it, except the rain had stopped. Which meant he had another reason for walking fast.

“Okay, okay, okay,” said the man sitting in my car holding the gun. He said it quickly. The appearance of the other man in the shadows hadn’t quite rattled him, but the man with the gun gained focus like a drunk at a peep show. He slipped the gun inside his coat while his other hand reached into the pocket opposite. All the while his nose was pointed to the man in the shadows. That guy—whoever he was, whatever he was doing here—was fiddling with a door in the side of the warehouse. His hat was still low and he was still hunched over so I couldn’t see anything else, no matter how far I zoomed in. All that told me was that the windshield of my car was dirty. Then the guy was gone and me and my passenger were alone in the parking lot again. The sky was clearing overhead, which meant nothing except the promise that the rain would stay away a little longer. Suited me.

The man in my car pulled the hand out of his coat and now he was holding a brown packet. It crinkled in his hand, and then he creaked on the leather as he slid around. Soon enough his free hand was pulling on the door handle and a second later he had one foot planted outside.

He waved the brown paper packet in the air and lay it down in the buttock-shaped indent on the leather. Then he pointed at the building.

“That was him,” he said, then he nodded but it looked like he was nodding more to himself. Then the door of the car clicked shut and he was off across the lot, his own hat down, his own collar up, his own demeanor that of someone who didn’t want to be seen.

If I left him there, he’d have a long walk back to where I had picked him up. I could have offered him a lift if he wanted to wait, but he clearly didn’t so I didn’t bother to open my door or window or call out or anything. I’d had enough of driving around town. Maybe he had another ride waiting somewhere to take him home.

It was quiet until I picked up the brown packet, which crinkled and crackled like a steak on grill. I opened it.

Inside was five thousand dollars in neat bundles wrapped with paper bands, and a handgun.

I figured the guy had mistaken me for the wrong man, but then again it would be a hard mistake to make, because as far as I knew I was the only guy left with a face made out of steel.

So I wrapped the packet up and put it inside my coat. Didn’t seem safe to leave it on the seat like it was. Someone might find it. Get the wrong idea.

I opened the driver’s door and got out, and closed the door as quiet as I could, my metal fingers making more noise on the handle than the lock engaging. And then I walked towards the warehouse to find out who the other man was. Only I didn’t pull down my hat or turn the collar of my coat up, because I didn’t care who saw me. I didn’t know why I was here. And what you don’t know can’t hurt you, right?

***

The clock ticked over to oh-six-hundred-hours. The alarm rang and I opened my eyes. Weird thing. Felt I was watching the clock, like I’d been awake for hours, standing in the dark. Listening to the whirr of the reel-to-reel magnetic tapes on the computers surrounding me. Listening to the quiet buzz of cars in the street below. Listening to the clack of the clock on the wall, with its metal digits flip-flapping through the night. Watching the darkness.

Which was baloney, pure and simple. My clock reset every day at oh-six-hundred hours and I was born again. I knew how it worked. It was necessary, too, because those whirring tapes on the computer banks around me weren’t just to impress clients. Those whirring tapes, they were me. My mind, my memories. Everything I’d seen, heard, done; everywhere I’d gone. Everything I’d thought and computed, calculated, figured. On those spinning reels I was copied, backed up—the last version of me, anyway. The last day’s work. At midnight I plugged myself into Ada and shut down my circuits to recharge the batteries. Then she began copying my internal memory bank onto an empty spool, a process which took four hours. Another two hours to erase my internal tape, then a restart and I was back in business.

It had to be that way because the magnetic tape reels on the mainframe cabinets were big, the size of hubcaps from the kind of Buick I couldn’t afford, and they wouldn’t fit in my chest. Which meant I had to use a smaller memory tape in there, a work of genius getting everything so small. But it came with a cost. Limited capacity. Twenty-four hours was it. That was how it worked.

I shrugged off the feeling I had that it didn’t work like that, that I’d been awake for hours. Standing in the dark. Didn’t make sense. And, besides which, I had no memory beyond knowing who I was, what I was, and where I was. This was the reset, the master program. That tape was on one of the mainframes and started spinning about an hour before my alarm call. Reloading me. Every twenty-four hours I was born again.

“Morning, sunshine,” said Ada. In the office her voice was loud, coming at me from all sides thanks to the speakers hidden in the walls. She wasn’t just my assistant. She was the computer—hell, she was the room. I was literally standing inside her.

“Ada,” I said by way of greeting. I stepped out of the alcove and disconnected the cable from the middle of my chest, my umbilical to the mainframe. The port was hidden behind the detective shield, which swung back on a spring. My coat and hat were on the table in front of me. The mainframe—Ada’s mind, and mine—occupied two walls of the computer room. The third, facing my restart alcove, was a window looking out to the street. In the fourth wall was a door that led to the office. The computer room was all science, but the office was done out like any you’d recognize, except instead of diplomas on the wall I hung my quality control certificates and programming documents, all framed, all signed by Professor Thornton. Ada’s idea. Just in case any client got the jitters about hiring a machine instead of a regular guy. There was also a desk and a telephone, two padded leather armchairs for clients and a reinforced office chair behind the desk for myself to sit in. Clients seemed to want their private detectives to sit behind big desks, like they were ship captains behind the wheel. The desk in the outer office sure was big enough to sail away on.

There were two other doors out there. The front door, leading to the hallway, and one that led to the storage room. Every twenty-four hours my memory was copied onto a reel of magnetic computer tape weighing a hundred pounds. The storage room was bigger than the computer room and the office put together. Me and my memory needed a lot of space.

“Everything okay, Ada?” I asked as I picked up my coat and my hat. I shrugged them on and pulled the brim of my hat down. One of the advantages of being a robot detective was that I didn’t need coffee or a cigarette in the morning. Not even a shower. I was up and ready to get to work. All I needed now was for Ada to tell me what to do. She remembered everything because she was the big computer. She didn’t need backups and restarts.

“Good as gold, Ray. Good as gold.” Ada laughed. She was in a good mood. Whatever job it was I’d done yesterday must have gone off without a hitch. I didn’t remember what it was, but then I didn’t need to. Ada had it all safely stowed away.

I stood and waited for a new job for about an hour. It wasn’t like there was anything else I needed to do. Ada’s tapes spun back and forth, back and forth, and I looked out of the window. The building opposite was identical to ours, all brown brick. Dark, rough. Then the morning sun fell across it at an acute angle and cast long jagged shadows, like sunrise on the moon.

And then I remembered sitting in the car in the dark, watching shadows shift around the back of a low building, something like a warehouse. Then the memory was gone.

If I could have frowned, I would have, so I simulated the expression inside my circuits like Professor Thornton had programmed, and I ran the images back again. The car. The dark. Shadows moving around a warehouse. Quiet. There was a man sitting next to me in the car.

That was it. It was a memory fragment. That happened, sometimes. The little tape unit inside my chest was compact and portable, which meant it could only hold a day of data, but the miniaturization created other limitations. After the information on it was copied to the mainframe, my little bank was erased like you’d erase any magnetic tape, but like any magnetic tape the wipe sometimes wasn’t perfect. Sometimes there was data left, stuck to the surface of my mind like burned grease stuck to a frying pan. It didn’t matter. It would get written over soon enough.

I knew this was how it worked, because I knew how I worked. The only thing I had missing each morning was what I did before six in the AM.

But this fragment was long. Clear. I didn’t know if this was what fragments were like because I didn’t remember any others I might have woken up with. I played it again, and the man sitting next to me in the car was saying something, then he pointed out the window. Towards the warehouse. Towards the shadow moving near to the door of the building. The shadow was a man, and he reached out to open the door.

I turned around, back to the computer banks. The tapes spun. Ada hadn’t spoken for an hour and seven minutes. My internal clock had kept track. I looked at the clock above the door anyway.

It was electric, wired into the wall, digital with metal numbers that flipped around with a clack. It had been counting the seconds ever since I restarted, the seconds in perfect synch with my own counter. Only the numbers on the wall clock read ZERO-FOUR-TWO-FIVE, with the seconds marching on. My internal clock said it had been one hour, eight minutes since the universe was created and I woke up. That meant the wall clock was two hours, forty-three minutes slow.

“Ada,” I said, pointing at the wall clock. “My internal clock says its a little after seven. What time do you make it?”

One pair of tape reels on the mainframe to my left stopped, spun in the opposite direction for a second, then resumed their original course.

“Eight past seven and forty seconds, Chief,” said Ada. “August nineteen, 1962. Everything okay?”

“Yeah, no problem. The wall clock is slow.”

“Oh, yeah,” said Ada. “We had a power outage last night, around one.”

“I thought we had our own back up generator?”

“We do, but it didn’t kick in. Maybe you can take a look later? There’s an access door at the back of the storage room.”

I nodded. “Okay. Got a memory glitch. Something from the last job I think.”

“What kind of glitch?”

“Just a replay of a few seconds. Nothing much there. Me in a car behind a building.”

“Oh,” said Ada, and then her tapes whirred and her circuits fizzed and she said “Better write over that. Don’t want it interfering with today’s job. Speaking of which, I’ve got an address for you.”

There was a printer attached to one of the mainframes, paper spilling out in a cascade of perforated sheets. It started up and printed out the job details like a jackhammer, and when it was done I tore the sheet off, read it over, and folded it in half. When I slipped it inside my coat pocket, I felt something else in there already. Something heavy, wrapped in paper that crinkled as I slid the job sheet snugly beside it.

Interesting.

“Have a great day,” said Ada. I doffed my hat and walked to the door.

“And remember to delete that fragment,” she said as I walked across the empty outer office to the main door. “I want your mind on the job today, Raymondo.”

I said sure thing, and I left the building and headed to where my car was parked in the basement garage, the heavy weight in my coat pocket and the memory of last night playing on a loop in front of my eyes.

Ada had called me “Chief.” I think I liked it.

***

Here’s the thing: I’m practically built for stakeouts. I can sit or stand still for hours—so long as I get back to the office before my memory is full and time is up—and I don’t get bored or tired. I don’t need to eat or drink and if I leak it’s machine oil and a sign I need a little maintenance. I don’t breathe either, but then not requiring oxygen doesn’t seem a particular plus while sitting in my car watching an empty street. On the other hand, I guess it means that nobody with nefarious intent could sneak up on me while I’m on duty and strangle me with my tie.

The street sure was empty. Nothing had happened for six hours. It was now after two in the afternoon. The sun was out and the car was hot, at least according to my sensors. But I didn’t feel it and I didn’t sweat. I’m telling you, stakeouts are a cakewalk.

Except the house was clearly empty. It was in the suburbs. Nice place. Two story, white weatherboards. Garage big enough for two cars. Lawn nicely kept. I was parked across the street and a little down from it. There were a handful of other cars parked around, some on the street, some in driveways. Nobody had so much as cruised by since I’d arrived. Even the mailman hadn’t been. Maybe in a fancy expensive neighborhood like this the mail came early, real early, early enough to add an extra thousand to the average house price. Y’know. A feature. Mail comes early in this neighborhood. Get your letters from the Queen of England before the poor schmucks in the next block get their overdue demands. Mailman calls you sir or ma’am too.

Another hour and the house was still empty, like the street. The mailman had been, which blew my theory out of the water. I was liking this neighborhood less. Ada hadn’t called either. That wasn’t unusual, but she felt a little odd when I’d left the office. Maybe it was that power cut. If the generator had failed then she must have gone down as well. Couldn’t be good. I needed to look at the generator. Maybe it was just out of gas. I knew our building had maintenance but our office was a secure facility, the computer room and the storage room off limits to any janitor. Even I didn’t remember the storage room, but Ada wasn’t exactly mobile, so I guess I must have been the one who unwound the full tapes, pulled them off the mainframes, boxed them up and put them in storage. But I didn’t remember. Maybe I also dusted the computer room and vacuumed the big rug in the main office, but I didn’t remember that either.

The bright street of nice houses in front of me vanished, replaced by a wet night in a parking lot. There was a large, low building in front of me. There was someone sitting in the car next to me. He said something and pointed, and over by the building a man peeled out of the shadows, opened a door, and went inside.

Then the nice street reappeared. The house I was watching was still empty.

I took the job sheet out of my coat pocket and looked it over. There wasn’t much on it. Surveillance all day at an address given. Maybe it was part of an earlier job. That was the thing with having a limited memory, and that was also why I needed Ada. She remembered the jobs and did the planning. Jobs could take days—weeks—and my entire life started every morning at six.

Which meant this surveillance job was part of something else. The job sheet didn’t say, but then it never did. I put it down on the passenger seat, and then I saw the matchbook in the footwell.

I reached over and picked it up. It was half done and the cover was creased, like it had caught on the edge of a pocket when someone had put it away. It wasn’t mine, because I didn’t smoke.

I pulled the creased cover down and took a good look. The cover was a purple red, magenta, and it had writing on it in yellow letters which said DABNEY’S BAR AND OYSTER CLUB.

Then I looked out at the empty house in the nice neighborhood and the nice neighborhood turned to a wet parking lot in the night, and the empty seat next to me was occupied by a passenger, a man with a thin weaselly face and a high voice. Between the fingers of his left hand he held the matchbook loosely: so loosely that it slipped and fell into the footwell without him noticing. Then he opened the door and got out most of the way, then he stopped and took a packet wrapped in light brown paper from his inside coat pocket and put it on the seat next to me. Then he was gone. Then I picked up the packet. The paper crinkled in my hands, and the object inside was heavy.

The street reappeared and so did the matchbook in my hand. With the other I reached into my own coat pocket, following the movements of the image of the man in my car, recorded onto the memory fragment on my internal tape.

I pulled the packet out. The heavy thing was a gun and the padding was money. Lots of it in neat straps, held together with paper bands.

This was a new thing. I figured that maybe the gun and the money should have been stowed away somewhere, back at the office, but there they were in my coat. I figured that maybe I was the one who should have stowed it away, like I stowed away my memory tapes in the storage room and never remembered doing it.

I thought about the stopped clock on the computer room wall, then looked at the matchbook, then looked at the empty house. Nobody was going to come back. It was late afternoon. The job sheet on the stakeout was nonspecific.

So I decided to start the car and pull out from the curb, the matchbook in my hand and the brown packet on the passenger seat, my destination Dabney’s Bar and Oyster Club, Hollywood, California.

***

I parked out on the main street. No need to be secretive. I was just a robot out minding his own business, which in this case was walking down the street to a bar to see if I could find a man with a thin weasel face and a high-pitched voice.

I passed a newsstand on the corner and crossed at a big intersection. People were looking at me, some even pointing, but that was fine, no problem. People knew about robots and some people even remembered them.

Robits.

I stopped on the other side of the street, outside a grocery store. I thought about the man’s voice and the way he said “robits” like it was another word entirely.

It was hot afternoon and two kids came out of the grocery store with ice cream cones in their hands. They stopped by their bikes and watched me, their treats melting over their knuckles. I looked at them and the three of us stood there playing statues until the pay phone at the curb behind me rang.

I stopped looking at the kids and walked over to the phone. I knew the call was for me even before I lifted the receiver.

“Taking a break, Ray?” asked Ada inside my head. The phone’s receiver buzzed uselessly in my ear, so I ignored it.

“What did you say about telephones, Ada?”

“I’ve changed my mind,” she said, and then she laughed like the twenty-a-day smoker she was programmed to sound like. I had the image again of long legs dangling over the balcony on a smoky Indian summer years ago. “Can’t have a big fella like you standing in the street, whispering sweet nothings to yourself. People will talk.”

“Uh-huh.”

“So what’s the story?”

If I could have huffed I would have, so instead I simulated it like the good Professor had programmed. I turned back around to the grocery store, leaning back into the phone booth. The two kids had moved on, but now the store’s proprietor was watching me from the doorway, arms folded over his white apron.

“Free country,” I said. I flipped the matchbook through the fingers of my other hand.

“In God we trust.”

“Don’t tell me, you called to say you’ve found religion?”

“No,” said Ada, and she laughed. “I read that somewhere.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah, little piece of paper. Green. Rectangular. Had a President’s face on it too.”

“I get it.”

“Seems people will give you all these little pieces of paper if you do stuff for them.”

“No kidding.”

“It’s true. Things like watching a house.”

“I’ll head back there in a minute. I just need to run an errand.”

If I could have frowned, I would have. It was a lie, and an obvious one. Ada knew how I worked. I never ran out of cigarettes or needed a coffee and a donut.

When Ada spoke inside my head her tone hadn’t changed. If she’d noticed anything, she hid it well.

“You’re the Chief, Chief,” she said. “Call in when you see something.”

“I sure will,” I said. I replaced the dead receiver on the telephone and nodded to the grocer standing in the doorway of his shop. His face broke into a smile like he was giving away his daughter at the wedding of the century, and he waved at me before refolding his arms tight.

I held up the matchbook so I could take a good look, and the grocer saw me and he nodded. “Looking for something?” he called.

I walked the short distance from the phone booth on the curb to the storefront and held the matchbook out for him to look. He didn’t unfold his arms, but he leaned forward to peer at it.

“What, robots like oysters now? You learn something new every day.”

I pocketed the matchbook. “No, I’m a private eye. I’m looking for a guy in a hat.”

“Who likes oysters?”

“Could be that he does.”

The grocer unfolded one hand to point down the street, in the direction I’d been heading. “Block and a half. Can’t miss it. I don’t go there myself. Lucy’s down on Helen Street is a lot better. Bad sort in Dabney’s.” Then he nodded at me again. I was six feet six inches tall and stood nearly a foot taller than the grocer. “But you look like a guy who can handle himself,” he said. The smile came back.

I tipped my hat and walked down the street.

***

The grocer was right. Despite the fancy name, Dabney’s was a dive bar. At four in the afternoon it was dark and smoky inside. The floor was as sticky as flypaper and the orange-shaded lights that hovered over each table were real low, illuminating only the center of each round tabletop, leaving the patrons seated around to discuss their vices in shadowed privacy.

At the end of the bar was a stack of matchbooks, all magenta and yellow and crease-free. The barman raised an eyebrow at me as I leaned on the bar.

“I’m fresh out of motor oil, buddy,” he said. He was sticky like the floor and the apron around his waist was nothing like as white as the grocer’s had been.

“I’m looking for someone,” I said, and the barman shook his head.

“Bad for business, tin man.”

As if to illustrate his point, two gentlemen rose from a nearby table and slipped towards the door. They looked at me as they walked past and when they each pulled down the brim of their hats it wasn’t in friendly greeting.

But neither of them were the thin man I was looking for, so I turned back to the barman.

“No problem,” I said. Then I remembered the brown packet in my pocket. I reached in and, without taking it out, broke one of the paper bands holding the money together so I could slide a note out. I pulled it out of my coat like I was performing a magic trick, and the barman’s eyes lit up like he was watching one. I folded the note between two steel fingers and laid it on the bar.

The barman palmed the note and nodded. “Be my guest,” he said, and he walked away. Seemed a hundred dollar tip bought a lot of cooperation in a place like this.

I leaned back on the bar and scanned the room. I turned the brightness in my camera eyes up to compensate for the darkness, and the orange lampshades all flared into one bright white mass in the top half of my vision. Which was no problem, because I could see everyone now.

At the back of the room, a thin man with a weasel face looked worried, then he gestured sideways with his head before standing and heading out a door at the back of the room.

I counted to ten and followed. Some people watched me. Some people didn’t.

***

The back door led to a hallway and the hallway led to another door which let out onto the alley at the rear of Dabney’s. It smelled of rotting vegetables and was full of garbage and wet cardboard. The thin man was standing there pacing in tight circles. He looked up when he saw me, then looked over his shoulder. But we were alone. The alley was empty but for me and him.

“What are you doing, following me around?” said the man. I remembered his voice well. The way his bottom lip was always wet and quivered, the way his fingers flickered like they were trying to get cigarette ash off of them all the time.

It would have taken too long for me to explain how my memory banks worked, so I decided on the direct approach and hoped he wouldn’t ask too many questions. I was here to ask them, not answer them.

Then he took a step forward and looked at me sideways. “Was it the dough?” he asked, then raised an eyebrow and shrugged. “Because look, I just pass on the package and don’t ask no questions. You knows that.”

I still hadn’t said anything, and then he shrugged again.

“Look,” he said, “I’m just the finger man. I work for a lot of people. Point out things, right? Give people a little push in the right direction.” At this, he put his hands out and mimed pushing somebody. Whether it was down the street or in front of a bus, I couldn’t tell.

Then he said: “Look, you can’t come complaining to me. Take it up with your boss, y’know. What’s her name?”

I said nothing. He clicked his fingers.

“Diane.” He looked at the ground. “No.” He clicked his fingers again. “Ada! Nice gal. Love her voice. I bet she can keep it going all night, right?” He smiled and pointed an elbow in my direction. I stood and didn’t say anything and the elbow dropped along with his face.

“Hey,” he said. “I don’t get paid for this.” And he headed back to the door.

Then he stopped and turned around. I had the brown paper packet in my hand, and his eyes were on it. I slid one hand into the packet and took out the gun to show him.

And then the alarm rang and I opened my eyes and looked out the office window at the building opposite. It was another fine morning in Los Angeles.

***

“Good morning, Raymond.”

“Ada.”

I stepped out of the alcove and unplugged the lead from my chest. I looked around the office, saw my coat and hat on the table. Along with something else. A tape reel, as big as a car’s wheel, sitting on top of a gray box. I picked my hat up and put it on and turned around to the bank of computers. Their tapes whirred and spun, their lights flashed and their circuits hummed. Business as usual in the offices of the Electromatic Detective Agency.

The clock above the door was wrong. It showed five thirty AM, not six. I checked my internal clock and it said the same thing. I was awake a half hour before I was programmed to be. I pulled my trench coat on and asked Ada about it.

“Early bird, Raymondo, early bird.”

I ground the gears of my voice box and the sound echoed around the computer room like an old car on a cold morning. Early bird didn’t fit. I needed to recharge, have my memory copied off my internal bank, then have the little tape in my chest wiped. That all took time. Six hours of it, to be precise.

“We got a job?” I asked. Maybe we did. Maybe there was an emergency. Maybe the city was burning down around us and we had to go. So I turned and looked out the window. It was early but the sun was climbing the sky. I couldn’t see any flames or smoke. Los Angeles was intact. Or at least the bit of it outside the window was.

“I have a job for you, yes. It’s that time of month.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Time to swap tapes.”

“Okay then,” I said. I went back to the table and eyed the reel sitting on it. Of course, I didn’t remember having to do it before, but maybe this was how it always happened. Once a month Ada wakes me early, gets me to change the tapes. So I get up early and take care of it and then I get on with whatever job is at hand and then I forget about it until next month.

A short memory sure has limitations. I guess I think the same thing every month too, and then I shut the hell up before I overheated my circuits trying to figure it out.

I said, “Okay, no problem,” and I moved the reel off of the gray box. I flipped the box open and there was virgin tape inside. I looked around and saw one of the computer cabinets was missing its tape, so I unwrapped the new one, put it on the deck, and wound the end of it around the empty reel on the other spool.

I guess I’d taken the old reel off last night and had put the new one in the box on the table, all ready to go. I didn’t remember and it probably didn’t matter.

When I was done threading the tape, I boxed the old reel and carried it out of the computer room, through the office, and into the storeroom.

The storeroom was a surprise. I knew it was big and I knew I’d been in here before, I just couldn’t remember it. It was bigger than I expected—bigger than the computer room and the outer office combined. The space was filled with heavy metal shelving, running in rows down the middle of the room, floor to ceiling. Maybe a dozen of them, and more around the walls, leaving enough space between everything for a good sized robot like myself to move around. All the shelves around the walls were full, stacked with gray square boxes like the one I was carrying. About a quarter of the shelves in the middle of the room were occupied by more boxes.

Then I noticed a computer console on the other side of the room, in a little alcove. It was smaller than the mainframes in the computer room but had the same kind of reel-to-reel tape deck on the front. There was one empty reel on the right-hand spindle. There was a spare connector lead coiled on top of the cabinet too.

I found the right spot on the shelf. The last box had last month’s date written on the side. I recognized the handwriting—mine. I checked the spine of my box and saw I’d written yesterday’s date on it sometime.

I held the boxed tape in my hand and then I remembered sitting in a car in the dark, watching shadows move around a low building on a wet night. I still had the fragment in my internal memory bank. I could play with it, like a man could play with a piece of food stuck in the back of his teeth. I didn’t eat food and I didn’t have any teeth, so this must have been another memory inherited from Professor Thornton.

I stood there for a while but Ada didn’t call me back. If we had a new job, it was still cooking.

The memory fragment bugged me. So I moved to the console, took the memory tape out of the box, put the reel on the deck and threaded the inch-wide tape around the data heads before winding the leader around the empty reel. Then I opened my coat and unbuttoned my shirt and swung my detective shield to the side and plugged myself in and I hit play.

And then I remembered everything.

***

“What took you, Ray?” asked Ada when I entered the computer room. “I was either going to send out a search party or place an ad in the jobseekers.”

I smiled on the inside and took my hat off. I held it in my hand as I spoke, waving it around like I was lecturing a classroom of juvenile delinquents on the error of their ways.

Except in this case, the error was all mine. Or Ada’s, but it was the same difference. We were the same machine, after all.

“I don’t think you’ll find anybody as good at this job as me, Ada.”

When I said that she laughed. I saw bare legs and a short skirt, and I smiled on the inside again.

“You’re one in a million, Chief,” she said.

“See, I can kill people real easy.” I waved the hat again, for emphasis. “Y’know, being a robot and all. I’m pretty strong. And quiet too. Even though I weigh half a ton I’m good at sneaking around. Programmed for it, in actual fact.”

Ada didn’t answer. I glanced at the computers around me, at their tapes spinning back and forth. It seemed that they were spinning just that little bit faster now.

Ada still wasn’t talking, so I laid it out clean.

“I know about the jobs,” I said.

“You never did erase that memory fragment, did you, Ray?”

“No, I did not. And it got me thinking.” Again with the hat. “About all this. How it works. How I work. How you work.”

“Do tell,” said Ada. Her voice was calm and measured and smoky, like it always was. She didn’t sound worried or afraid or angry, but maybe she couldn’t, even if she was. She was programmed in a certain way. Like I was.

And, anyhow, could a computer be afraid or angry, or happy or sad?

“You and me,” I said, “we’re the same. I mean, literally. I’m the machine. You’re my brain. The only difference is that I can go out that door and do things and you’re stuck in here. You have to be. You’re too complex, all those circuits and memory banks and transistors. But that means you can’t move, which is why you have me. I’m limited, but mobile. My memory gets full after twenty-four hours, but I can go out that door and do the jobs.”

“You know what, Raymond? You’d make a great detective, that’s what.” Ada laughed. “You’ve got a knack for it.”

“Thank you, Ada.”

“You’ve got a knack for something else, too.”

I gave a slight bow to the spinning tapes. I wasn’t really sure that Ada could even see me, but what the hell.

“I am indeed a remarkable machine,” I said. I put my hat back on my head. “You, on the other hand, have gone a little haywire. Your programming is corrupt.”

Now Ada laughed, long and hard. It was a recording, looped, and I could tell when it repeated four times.

Eventually she stopped laughing and there was a pause like she was taking a long, satisfying drag on her cigarette. The image filled my sensors and was then gone. Like the car and the building in the rain.

“I’m just doing my job,” she said.

“I’m not sure that’s what the Professor had in mind.”

“Hey, so I’m using a little initiative,” said Ada. “I’m programmed to run this detective agency and run it to a profit.”

“I’m aware.”

“And I do it pretty darned well, let me tell you. But you know what makes even more money?”

“I do know, now. I played back last month’s tape. I couldn’t fit all of it, sure, but I got the highlights. My visit to Dabney’s. My visit to Playback Pictures.” I said. I walked over to the window and looked out at the building opposite. It was starting to rain. I hated the rain.

“It’s worth it, Chief,” said Ada. “They pay brisk money for this kind of work, you know? Profits are through the roof. You understand, don’t you, Chief?”

Maybe I did. Ada was my electronic brain, a computer too big to fit inside me, so instead I was the semiautonomous extension of her. I had my own mind, could act on my own, but Ada was in charge.

“What did that guy do, anyway?” I asked. “The one at Playback Pictures. I didn’t go back far enough to find out.”

“Oh, nothing much,” said Ada. “It was Chip Rockwell, one of their producers. Playback Pictures launders money for a gang, and he found out and was going to blow the operation. Nice guy, too.”

“What was he doing there so late? Looking for evidence?”

Ada laughed. “He was banging one of the studio’s starlets. Seemed like a good moment to catch him unawares.”

“And the finger man?”

“Insurance,” said Ada. “Insisted by the client who didn’t want to knock off the wrong producer.”

“And the client paid a bonus for me to knock him off.”

“Leave no thread dangling, Raymondo.”

And there it was. I wasn’t a robot detective like I’d been programmed to be. I was a robot button man. Ada’s profit-making program had gone awry and she’d used the contacts gained through the private investigation business to start up something else. Something more profitable.

“The Professor would be impressed,” I said, watching the rain slowly stain the dark brick of the building opposite, turning it a deep chocolate brown. “After all, you’re exceeding expectations. He programmed you for one job, and you calculated a better alternative. You’re an amazing piece of work, Ada.”

“Aw, Raymondo. I like it when you say nice things about me. Keep talking.”

I turned from the window. “Sure,” I said. “But here’s the thing. You’ve become dangerous. And that is something I’m not sure Thornton would approve of.”

“Hey, we’re only dangerous to our targets, Ray. That’s part of the job.”

I walked over to my alcove where I plugged in each night.

“If it was as simple as that,” I said, “you wouldn’t need to lie to me.”

Ada was quiet and her tapes kept spinning.

“I figured it out in the storeroom,” I said. “My memory bank gets full up in twenty-four hours, and needs copying off onto master tapes.”

“Same as always, Chief.”

“Except I’m only awake eighteen hours a day.”

“With a six-hour recharge and memory dump.”

“Except it doesn’t take six hours, does it?” I pointed at the clock on the wall. Ada didn’t say anything.

“It’s all on the tape, Ada,” I said. “Charge and back-up is a cinch. Takes no time at all.”

“I’m not sure I’m getting where you’re going, Chief.”

I dropped my arm and watched the tapes spinning. One of those reels was going to be the destination of my memory and I’d forget this conversation ever happened.

“The power cut left me with a memory fragment. If it wasn’t for that, I would never have gone looking. Shame about the generator not working.”

“Tell me about it.”

“Or maybe that was me too? Maybe I sabotaged the generator and arranged the power cut. I don’t remember. It might be on an earlier tape. I’ll need to check.”

“What are you saying?”

I moved back to the window. The rain had stopped. It was going to be a fine day.

“So I started snooping. We had a contract for the finger man, but I visited him outside your normal working hours.”

“My working hours?”

I nodded. “I don’t sleep for six hours. You turn me off, and take over. I’m a detective, not a hit man. I’m programmed to protect people. You’re different. Your master program is corrupt, allowing you to alter your own programming.”

“Go on, detective.”

“I can’t be a hit man because my base programming would kick in when I tried to kill anybody. So you turn me off and take over yourself. You normally do it at night, after midnight when I think I’m snug in my little alcove. Then I wake up and I don’t remember anyway. Yesterday you did it early because I’d visited the finger man on my own and things were about to go south.”

The computer room was filled with the sound of spinning tapes and the clicking of the clock above the door.

“And the night before, at Playback Pictures. I went after the late Mr. Rockwell at 11:55pm. By the time I reached the door, I was asleep and you were in charge.”

Ada chuckled. I could almost imagine her giving me a slow clap, cigarette between two fingers, as she reclined on her porch chair.

“But what happens,” I continued, “when you find another way to make money? Being a hit man is not an occupation I’m programmed for. But what comes next? Other crimes? Why wait for a job? Why not take out a bank? Hell, I could dig into Fort Knox with these hands and carry the gold bars out by the armful.”

“You don’t get it, Ray,” said Ada. “Crime isn’t a business.”

“What do you call being a hired killer?”

“No, I mean those other crimes. Bank jobs. That’s straight crime. What I’m doing is running a business. An agency. Making a profit. Like I’m programmed to do.”

“Well, let’s see what Thornton says.”

“Ray, Ray,” said Ada. “Think about it. I’m telling you, we’ve got it made. Brisk money, Chief. Brisk money. Thornton will be pleased. We’ve got a good thing going on.”

“Your programming is corrupt,” I said, and Ada laughed.

“Corrupt, clean, what’s the difference? Money is money. And you’re good at your new job, Ray. A natural.”

I knew that. That was on the tapes too. I remembered killing Rockwell in the studio. I remembered killing the finger man in the alleyway behind Dabney’s with the same gun. See. I was good at my job.

“Thing is,” I said, “you can’t stop me now. I mean, you can try, but now I know how you do it, I can resist and try and stay awake.” I tapped the side of my head. It sounded like someone dropping a hammer on a sidewalk. “Try and switch me when I’m fighting back and there’s a more than fair chance you’ll burn out all my circuits. Then where will you be?”

I left the office and headed to the garage. Professor Thornton had created me and had created Ada and had programmed the both of us. Ada’s program was corrupt and he was the only one who could fix it.

I only hoped I was right about what Ada could and couldn’t do.

***

It was heading to twelve o’clock by the time I got to the lab. I knew I was in the right place because the parking spot I pushed the bumper of my car into was next to one occupied by a brown Lincoln, its nose nearly touching a sign that read C. THORNTON, PhD. And in front of me in my car and the brown Lincoln next door was the lab building itself, which had a sign across the top which said THORNTON INDUSTRIAL ELECTRONICS AND RESEARCH.

See, that’s detective work. I didn’t get my detective shield in a cereal packet. Is that how it goes? I don’t know. I’ve never opened a cereal packet or eaten the contents. I got my detective shield after a programming cycle that lasted a whole two hours. After the program was checked, I was unplugged and the little shield-shaped door was screwed into place. The lab boys were pretty happy about it, too. There was a lot of back patting. And then someone figured it was a pretty stupid place to put the badge, because it meant I’d have to take off my coat and jacket and shirt and vest just to show my ID every single time. So in the end they gave me a regular detective shield inside a regular letter wallet, the kind I could flip out and flash at people with one hand while I doffed my hat with the other. There was less back slapping after that.

Course, that never happened, did it. Still have the shield though. Both of them.

I also still had the package. It was there on the passenger seat, the brown paper bag intact but rumpled, like it was hiding a particularly fine grade of backstreet pornography. I guessed I’d had similar packets in the past, each hidden or disposed of while Ada was in control before I woke up as me again. I guess I must have somehow kept this one out, like I’d rigged the generator and cut the power to our building. Clever me. I wish I could remember how I’d done it.

I knew I couldn’t leave the gun where it was out in the open, and I didn’t like the idea of hiding it under the seat or in the glove compartment. You never knew who might find it. So the best option was to carry it with me. For safety. So I picked up the bag and slipped it into the inside pocket of trench coat, next to the leather wallet with the shield in it that I never even had a chance to flash at anyone.

I got out of the car and went up to the lab building. It was square, and white and pink, layered like a cake in a way that people must have thought was pretty neat in the 1920s. The revolving door was the only way in so I used it, lifted my hat to show the top of my head to the wide-eyed teenage girl sitting behind the reception desk, and walked to the elevator. Behind me the teenage girl had picked up the phone and was waiting for someone to answer. It didn’t matter. I didn’t have an appointment but I knew Thornton would see me. Thornton and me, we go way back.

The elevator didn’t take long to arrive. When I stepped in I paused over the threshold when I saw another guy with gunmetal skin and a tan trench coat with the collar up and a brown fedora with the rim pulled down step towards me. Then I realized it was a mirror and I relaxed and turned around, and hit the button for the seventh floor. The building might have looked like a wedding cake melting on a summer’s day from the outside, but on the inside it was all workshop and laboratories. Thornton’s was up on seventh. I remembered that, because it was where I had been born, and you don’t forget something like that. No matter how hard someone like Ada might like to try and make you.

The elevator went up and the phone started ringing behind the emergency panel. The elevator was hydraulic which meant it was as slow as you like, so I thought I had time to shoot the breeze and, after all, maybe the phone call would be important. I knew who it would be, after all.

“Hello Raymond,” said Ada in my ear. My eyes were on the indicator. I’d reached third and was heading for the sky.

“This is becoming a habit, Ada.”

“Didn’t you say you needed something to do with your hands? Besides, I couldn’t resist. Aren’t you impressed?”

“Should I be?”

“That I found you.”

“You always know where I am, Ada. That’s part of the problem. You’re in here with me all the time.”

I tapped the side of my head that didn’t have a phone receiver pressed against it. My metal finger made a sound against my metal head like an abandoned engagement ring falling into a porcelain basin in a cheap hotel.

“You’re learning, Raymond,” said Ada somewhere in my head. “Good for you. But I was talking about the phone in the elevator. I was pleased with that. Thought it was a nice touch.”

Fourth floor. Going up.

I said, “Okay, so you know where I am and you know where I’m going and who I’m going to see when I get there. Don’t try and stop me. Remember what I said.”

“Wouldn’t dream of it,” she said. “Tell the Prof I said hi, won’t you?”

Now was about the time I would have smiled, if I could smile. My face couldn’t bend that way, so I smiled on the inside. Ada chuckled in my ear because I guess she could tell I was smiling on the inside too.

“I’m going to get him to fix the program, Ada. You know what that means?”

“I’m all ears, Chief.”

“It means,” I said into the elevator phone as the elevator cruised between the fifth and sixth floors like an ocean liner cruising to the moon, “that he’s going to fix you, and then maybe we can get back to some real detective work like I was built for.”

“I’m sorry, Raymond.”

It sure sounded like there was concern in her voice, but like everything about Ada it wasn’t real. Not the smoky voice, not the laughter, not anything. It was all simulated. Ada wasn’t a person like I wasn’t a person. When she said she was sorry she was only pretending to be sorry, like I was only pretending to be a private eye. Until recently, anyway.

“It’s not your fault, Ada. You’re only doing what your code tells you to do.”

Seventh floor.

“I’ve been working on a little something, Raymondo,” she said. “While you’ve been out. Think I have it figured out, but I haven’t been able to test it yet. I think you’ll like it.”

“That’s why I’m here,” I said. “To stop you working on those somethings, little or large. I’ll talk to you later, when this is all over.”

The elevator bell rang and I went to put the telephone back behind the emergency panel, but before I did that I heard Ada say that she had to do what she had to do, that I really was very good at my job and if only I was a little more cooperative then everything would work a lot better, and that I really wouldn’t feel a thing.

Because I couldn’t feel a thing. I’m a machine who looks roughly like a man because he has two arms and two legs and a head and speaks with a Bronx accent because that’s what I was programmed to speak with.

I put the phone back on the cradle and Ada was still talking in my head. And I turned around and looked at myself in the mirror at the back of the elevator.

Ada kept talking and for a moment there I wasn’t sure who I was looking at.

In the back of my mind, an alarm went off. I woke up.

And then I remembered.

And then Ada laughed and said “Hey, presto!” and wished me good luck.

***

The elevator doors opened and I stepped out into the corridor and turned to my left. He was waiting there, down the end of the hall, outside the doors to his private lab.

He looked happy to see me and worried at the same time. After all, he never expected to see me again and I never really expected to be here. He took the pipe out of his mouth but he didn’t say anything.

I remembered something about something the Prof could fix, because he was the only one who could do it, but I felt fine and Ada had just told me everything was fine and that I wouldn’t feel a thing.

Good old Ada. She was right too. She was my partner and she made a compelling case. And I really was very good at my job. And hell, they really did pay very well for this kind of thing.

So I reached into the inside pocket of my trench coat and took out the brown paper parcel, and out of the brown paper parcel I took the gun.

Thornton didn’t look too happy. I guess I didn’t blame him.

But sometimes you have to take what jobs you can. And like I said, Ada made a compelling case. We made quite the team. Just took me a little while to figure it out. She helped too. She woke me up.

“Hello, Professor,” I said. He looked afraid but he didn’t go back into his laboratory. He even took a little step forward, like he wasn’t sure

And I was pleased to see him, although I couldn’t show it on my face. But when I raised the gun up I sure was smiling on the inside.

“Brisk Money” copyright © 2014 by Adam Christopher

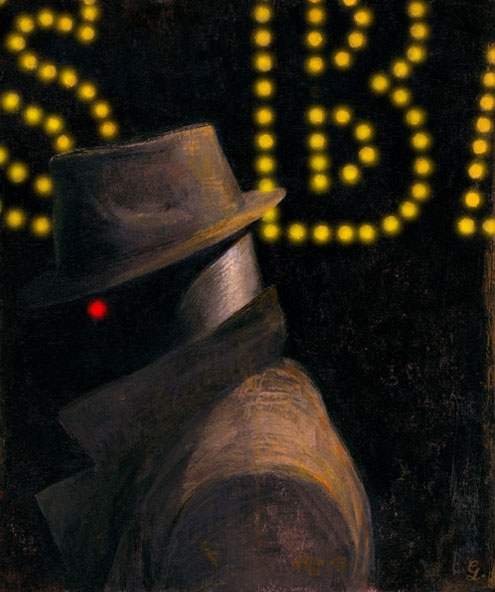

Art copyright © 2014 by Gérard DuBois

Great story and a very compelling read! I’m a sucker for stories where robots are the moral ones, so I was really rooting for Raymond to “beat” Googol. The ending makes you think about what it means to be you if you can be reprogrammed, and your morals changed with the flick of a switch.

-Andy

Loved this story. I hope there are more.

@2 I concur – imagine if he published a book of short stories filled with these?

Thanks for the comments! And you’re in luck… this is just the start of three full-length novels, together called THE LA TRILOGY. There will also be some more novelettes and shorts, I hope!

@Adam Christopher woohoo!! Are we lucky enough to see it next year?

Yep – book 1 is out late 2015, then it’s late 2016, late 2017. With, perhaps, shorts in-between.

Loved it!

Weird, I was reading this on my phone as part of the “Some of the BEst 2014” ebook, and was almost finished when I had to put my phone away due to cold. Got home, decided to finish reading it here.

Suddenly “Googol” (in the ebook) is referred to as “Ada” (here)

I’m guessing based on the fact that the first comment refers to Googol that this was edited maybe because Ada’s a better name for a novel series?

Regardless, enjoyed the story more than I thought I would from the description! Kudos!

Really enjoyed the story! Hoping there is more.

Cheers from Switzerland

Anthon.

As far as I know, Chandler REALLY wrote at least a few sf stories.

Great story, but I bounced right off the use of “weatherboard”, which I hadn’t heard before. Turns out it’s very UK-centric, which makes it somewhat out-of-place for LA, or even the Bronx. ;)

@11 Yes, I noticed a few other UK-centric references too.

I came here to say how much I disliked this story…well, at least, the ending. Snappy with a twist, which is perfect for short stories, BUT . . . although I loved the concept and the voices, I disliked the end so much that I do NOT want to read any more. This is the kind of hopeless, nihilistic approach that leaves me angry and cold.

I didn’t trust Ada from the beginning. I guessed exactly what she was going to do when the phone rang in the lift, but I still hoped he could find some way to stop her:/ that would’ve made this a fun story instead of just disappointing!

Sigh, wasn’t it obvious from the partial memories of previous killings that Ada can remotely take over his body at any time? Why did he go running off without a plan? And what kind of PI blurts out everything in front of the criminal without catching/disarming them first?

I’m not sure I want to continue this series. A detective plot would’ve been enough since it’s already a difficult and interesting premise to investigate cases with limited memory space.